Have you been seeing the phrase “late capitalism” pop up a lot lately? The term was originally attributed to German economist Werner Sombart referring to economic, political, and social deprivations associated with the aftermath of the first world war. The way we see it used in 2023, late capitalism has come to refer to an absurdist level of consumerism. And it’s in this environment of late capitalism, surrounded by $2,050 Balenciaga plush snake neck noodles and celebrities that openly mainline diabetes medication for weight loss, that the de-influencer movement came to power.

The de-influencer movement is a hybrid of the next-gen desire for accessible celebrities and the social element of online product reviews. Let’s take a look at how de-influencers came to be, the issues they shed light on, and how retailers can benefit from it without risking consumer trust. Let’s dive right in.

De-influencers tell customers not to buy certain products, only to recommend cheaper –– often sponsored –– alternatives. There are also concerns that de-influencers are being used to help certain brands achieve market domination, by taking down competitors’ inventory.

“Eat the Rich” Replaces “Let Them Eat Cake”

We’ve long known that Gen Z revels in breaking down old guard consumerist norms. Buying brands to fit in isn’t a thing for this generation of spritely rebels. And celebrities that function as untouchable icons? No thank you. Gen Z wants their celebrities to share about their personal struggles on Instagram Live. In fact, today’s celebrities can gain more traction by denouncing the toxic elements of normcore than conforming to them.

My first taste of what would become the de-influencer movement was when Salma Hayek told readers she used “nothing” to achieve her incredible skin. Over a decade later, wealthy, glamorous celebrities have been replaced by “eat the rich” storylines. There’s an onslaught of one-percenters getting their comeuppance on tv and in film, from Parasite and The White Lotus to The Glass Onion and Triangle of Sadness. But trendily denouncing these capitalist norms doesn’t end with popular entertainment.

What Exactly is a “De-influencer?”

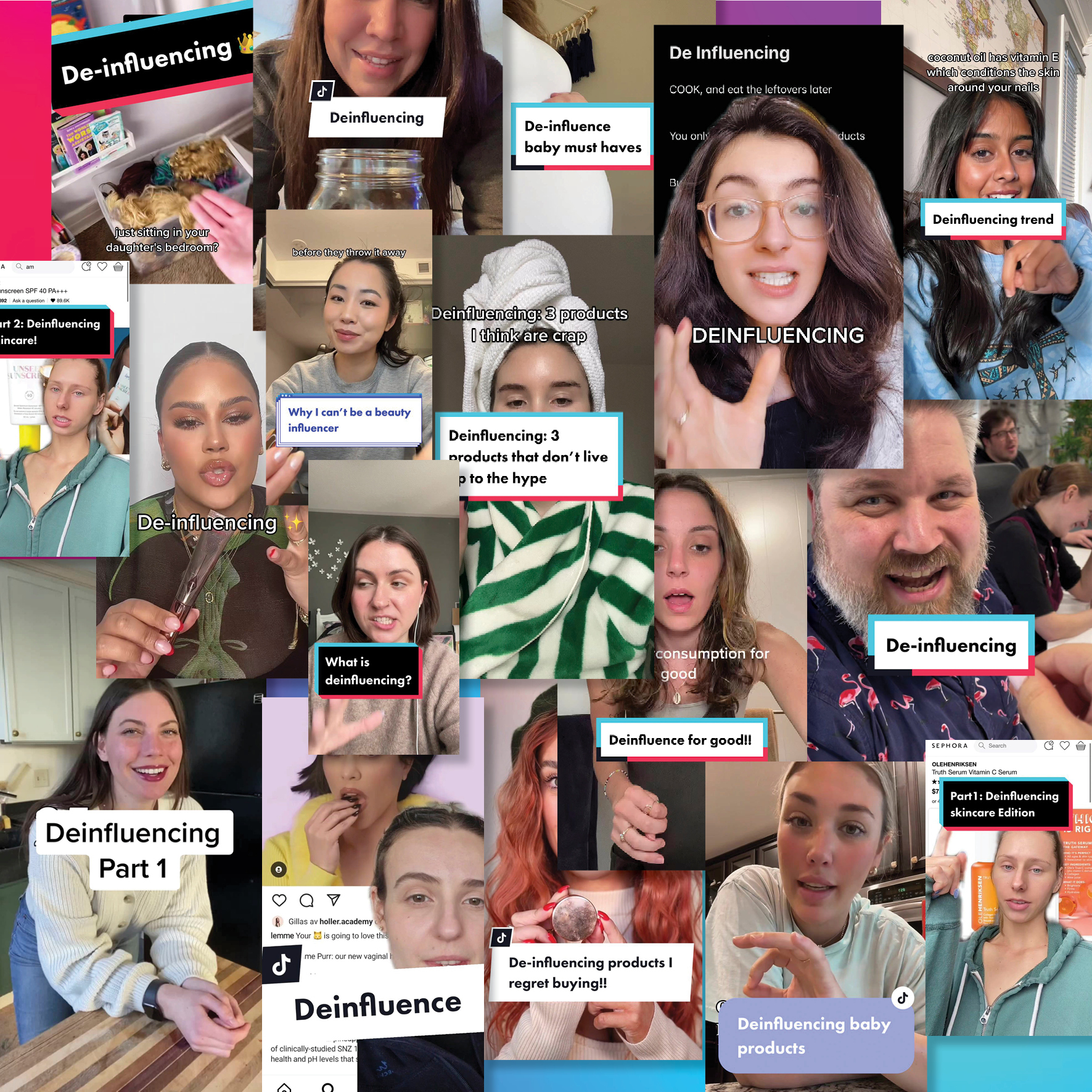

Gen Z is staging a war against conspicuous capitalism on TikTok. Hashtags like #TikTokMadeMeBuyIt are giving way to pleas to make 2023 the era of #Deinfluencing instead. But what, exactly is “de-influencing?” The term was created by young content creators on social media to describe how to encourage consumers to reuse products and buy less. The goal? Anti-consumption to save money and save the environment.

“De-influencer” is now also being used to describe influencers openly disparaging specific high-priced items on social media. The trend was started by everyday folks encouraging other everyday folks to consume less. Whether it was mocking specific off-the-rails fashion trends –– there are many to choose from these days –– or showing off low-priced alternative to trending items, de-influencers had an anti-consumerist aim. While there are plenty of authentic de-influencers trying to help their followers better their lives through more strategic purchasing, there are also a bevy of faux de-influencers, hiding the sponsored nature of their posts for financial profit and social accolades.

Pay Disparity Plagues Influencer Marketing

It’s hard to talk about de-influencer marketing without addressing the glaring disparities that the overall influencer marketing industry has yet to address. Influencer marketing can be a way for brands to tap into niche audiences that they couldn’t access with physical stores. Social media has been a hub for LGBTQ+ and non-binary people to find community since the advent of chatrooms (AOL, anyone?). That said, influencer marketing also reflects many of the glaring racial biases that impact other industries, without initiatives to reduce those discrepancies.

For example, Black influencers made 35 percent less than white content creators in 2021. There’s also a 29 percent racial pay disparity between BIPOC (black, Indigenous and people of color) influencers and their Caucasian counterparts. The FTC has no way to regulate the pay disparity. They can’t even successfully regulate every secretly sponsored post. Influencer marketing is, by nature, a surface level industry. For every heartfelt reveal video posted by a rural teen, there are ten micro influencers trying to sneak unlabeled sponsored posts onto their followers’ feeds. It’s the FTC’s inability to right these disparities that make the influencer/de-influencer/faux de-influencer field so difficult to navigate.

Is De-Influencing a Cheap Play for Consumer Trust?

Influencer marketing is maturing, and de-influencing seems like a new movement to make social media more beneficial to the people it serves… at least at first glance. Here’s the issue: Faux de-influencers tell customers not to buy certain products, only to recommend cheaper –– often sponsored –– alternatives. There are also concerns that faux de-influencers are being used to help certain brands achieve market domination, by taking down competitors’ inventory. Since the FTC is nowhere near being able to identify and penalize every unlabeled sponsored post, de-influencing is still the Wild West of retail marketing. And as always, it will take frontline consumers a few years to catch up with this practice.

Consider that 61 percent of consumers trust influencer recommendations –– particularly those of compulsively transparent micro-influencers who come across as “real people.” Now imagine how much consumer wallet share will be thrown at products advertised with faux transparency and faux “non-biased” reviews by faux de-influencers before the FTC catches up with the trend.

It’s not all the de-influencers’ fault, either. They need followers to drive lucrative collaborations, but they need sponsors to pay them for the work they do. Phys.org calls this phenomenon “role conflict:” when an influencer’s followers expect them to post transparent, unbiased recommendations, but brands expect the influencers they hire to portray their products in a positive light. Make no mistake, brands are already paying de-influencers to trash their competitors without disclosing their affiliation. Yes, this is unethical. And yes, it happens every day.

What’s an Honest Retailer to Do?

There’s no need for authentic retailers to go over to the dark side of undisclosed sponsorships. Like all nefarious business practices, faux de-influencers will be short lived. Just consider it another pin in the influencer marketing bubble that’s already at bursting point. Consumers will realize which influencers are misusing the de-influencer trend, there will be large scale boycotts of those that did, and some of the backlash will hit the brands that took advantage of this practice.

Callout culture will most definitely catch up with this practice and retailers will want to be on the right side of history when it does. In the midst of this chaos, honest retailers can continue to use transparency to their advantage by focusing on grassroots initiatives like giving back to communities and partnering with cause-driven brands.