With just a single year under its belt, Brandless, which prices all its roughly 300 products at $3, is reportedly valued at nearly $500 million, which is more than what Walmart paid for Bonobos. Some pundits have even touted Brandless as the most significant “Retail Disruptor” of the past year.

The whole thing is mind-blowing. Perplexing. Is Brandless a retailer? Is it a consumer product goods company? Is it something else? Or, is there a reason I feel like Macbeth, seeing not a dagger before me, but the Pets.com sock puppet circa 1999 staring me in the face?

Startup Economy on Overdrive?

The Brandless valuation is just a little too much to swallow, too soon. Having lived through the .com boom and bust in San Francisco in the late 1990s and the early part of the millennium, the current situation makes me wonder if investors are losing sight of how to value companies for what they really are and for what they really do.

There is some evidence that this question is warranted. SVB Financial in their recent quarterly conference call reported that the amount of venture capital investment in 2018 is “on pace to potentially exceed $100 billion for the first time since 2000.”

(Dramatic Pause)

The recent tumult in both the retail and the CPG industries may be leading people to believe, similar to the late 1990s, that new models of business provide more value than they actually do.

I can remember the conversations back in the 1990s – people thought, “Hey, we can eliminate the middle men and unlock a tremendous amount of value!” Flash forward nearly two decades later, and I can count on one hand the number of successful direct-to-consumer retail companies that have reached sustainable profitability in the long-run. As my professor in business school, Steven C. Wheelwright, said right after the .com bust, “You can find ways to improve the cost efficiency of how middlemen do their jobs, but you cannot remove their roles entirely. Their roles exist for a reason. That was the mistake .com investors made.”

The confounding issue this time is not eliminating fulfillment costs but middleman marketing costs. The barriers to entry for new brands or retailers are not what they once were – which is why we have seen such tremendous growth in the long tail of e-commerce. But it is deceptive to think that anyone can just put up a website, hope something goes viral at hot prices, and voila!

The economy could be overheated and Brandless is an example of a business that is overvalued compared to its long-term strategic value. In the long run, it is hard to see how Brandless can become the next big thing in retail when it is really just a retread of an old idea we have seen before – the infomercial.

The Rise of the Infomercial

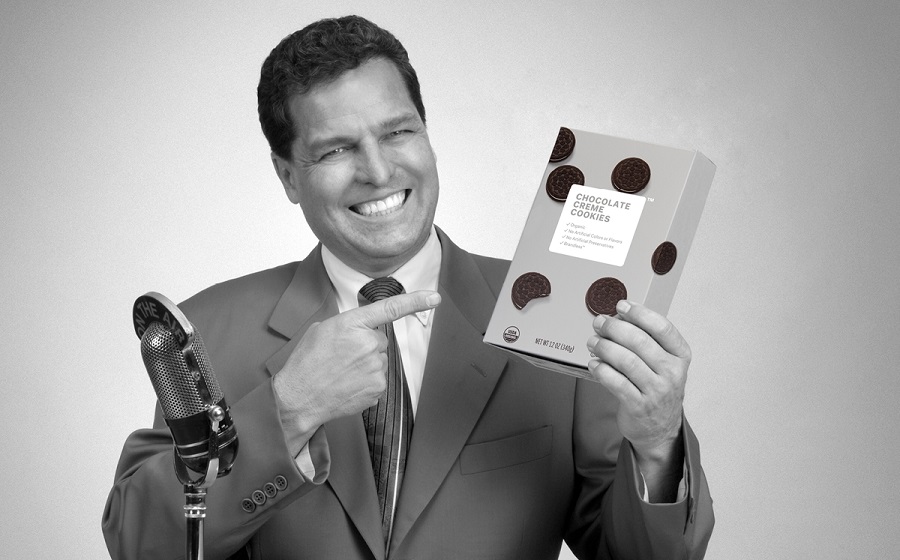

Put on your nostalgia cap. The infomercial, also called direct-response television (sounds germane, huh?), originated in the 1950s, but really hit its stride after 1984 once changes in FCC regulations took effect. The art form took off like a rocket ship in the 1990s.

Infomercials are long-form commercials, typically 30 to 60 minutes in length. The general idea is that products are sold by enticing TV viewers to call a number and to take advantage of a great limited-time deal, a deal often slung by slick pitchmen, like the famous Ron Popeil or Billy Mays. Just like in e-commerce, the consumer’s reaction to these advertisements is immediately quantifiable.

The allure of the infomercial was that it allowed companies or entrepreneurs to market their products in more cost-effective ways. It was based on a dreamy promise of creating that next great thing that entrepreneurs believed deep in their souls everyone had to have. This is counterintuitive because these products landed in infomercials because retailer after retailer had already rejected them. This resulted in infomercial products that seemed fresh because people had never heard of them. However, these products were often judged by the public to be gimmicks hawked by slick sales artists (see the Shake Weight®).

Now, that isn’t to say that there wasn’t a ton of money to be made in this model. But the products that were deployed were usually fleeting success stories (reported lifespans on infomercial-type products generally ranged from one to five years at best). Despite their better judgment, consumers did not really need a slap-happy plastic guillotine-like contraption to slice their onions or the ability to fit a garden hose into their pockets.

Brandless is Just a Modern-Day Infomercial

The phrase “direct-to-consumer brand” is flawed. It is too broad. The Thighmaster is, by definition, a direct-to-consumer brand. But to utter “Thighmaster” in the same breath when describing a company like Ocado is almost nonsensical, no matter how much one likes Suzanne Somers.

By the same token, we should not begin confusing Brandless with the other successful “direct-to-consumer” brands like Warby Parker, The RealReal, or Harry’s that have come before it. Brandless is more Thighmaster than it is a retailer or long-legged product company.

Like an infomercial for the modern age, Brandless appears to.be riding an ephemeral wave, buoyed by the easy access to e-commerce, social media influencer marketing, a beautiful package design and its slick “BrandTaxTM” marketing handle, which ironically also claims to eliminate middleman costs.

Let’s scenario-play the future. Here are the range of options in front of Brandless:

Survive as a direct-to-consumer brand? History, as already discussed, has shown this is tough, and especially at $3 price points.

Open stores? This move might feed the infomercial zeitgeist, but it could also make consumers lives more difficult. Consumers do not want to be forced to go to another place to pick up their household items. They want the convenience of being able to get their weekly needs all in one place. Even if they love Brandless beef jerky, going to a Brandless store when they still need to pick up fresh meat for the week somewhere else would then become an added inconvenience.

Secure new channels of distribution? This path is the most likely path. But it too will be a tough go. Much of what Brandless offers is commensurate with private label products already on the shelves of grocers and mass merchants across America and especially overseas. The only difference is that Brandless has converged everything to a $3 price point. Retailers will have trouble stomaching the margin structure of this price scheme and will also likely be reticent to give shelf space to products that are facsimiles of their private label lines.Oh, and then there is Amazon and voice commerce too, which could soon render Brandless and many other low-priced commodity brands irrelevant. This is not the outlook of the next great “retail disruptor.”

No matter how one slices it, it is hard to extrapolate how Brandless will become anything more than a product company that will face a number of profitability roadblocks at every turn in the future. The only course may be to do exactly what the company is doing – to act like an infomercial. It can press the gas on the marketing wave and then get out at the right time after making gobs of money off of the impressionable public.

The big tell, if I am anywhere close to the bullseye, will be if Brandless runs Super Bowl ads in January 2019. That is the litmus test for whether the money from the recent investment round will go to foundational work or instead be used to fuel the marketing machine even further. It will be proof that we may be living 1999 all over again.

Conclusion

It is easy to get swept up in the startup euphoria, which is why we have to dig deeper. Brandless could make people a ton of money. But that is not the point. With all the new direct-to-consumer classified brands that have already come our way or that will come our way in the future, we have to ask, “Are they true breakthroughs? Or are they just a new twist on an old form of marketing that teases us into thinking that they are something more?”

Brandless could become an example of a just-okay concept enabled by money running rampant. The investment and retail communities must take a more critical eye towards businesses as they pop up, lest they actually accelerate the pace of infomercial-like fervor and give rise to a .com bust Part II.

A can of spray paint is just a can of spray paint, but, in the hands of the great Ron Popeil, even the smartest among us can be convinced that a can of spray paint is really hair.

Note: This article should not be construed as investment advice, it is solely the opinion of the author.